What to read if... it's midsummer

Something entrancing to get lost in, obviously: so, here are The Makioka Sisters (Junichiro Tanizaki), as promised.

There are four of them, but the novel revolves principally around three of them, living in Osaka (the eldest sister, Tsuruko, lives in Tokyo, representing with her husband the “senior” house); and focuses on two, in particular (Sachiko - married to a prosperous accountant, Teinosuke - and Taeko). They're from a once prosperous merchant family - now so diminished that the only way to continue the family name is for two of the sisters’ husbands to take it - the business is long gone. The ostensible narrative thread (plot driver would be too crude a description for such an elegantly discursive, immersive, expansive work) is the necessity to arrange a marriage for the second-youngest sister, Yukiko - who's no longer young (contextually, of course, she's thirty); and whose single state (according to the conventions) is blocking her youngest sister, Taeko’s marriage.

So far, so Jane Austen - and, in some respects, it's not an unhelpful analogy. There's all the panoply of ritual matchmaking, including the helpful (but strictly amateur, so a certain elegant “naturalness” in her involvement) Mrs. Itani (owner of a beauty salon); the miai - first exploratory meetings between the parties, (literally “look meet”); the private investigators (standard). The detail: both domestic and social.

But to cling too closely to that analogy does two great writers a disservice. Tanizaki is entirely his own man; and this is a vast work, in every sense (a luxurious near 600 pp); generally acknowledged as Tanizaki’s masterpiece. There are (apparently) people who argue - sometimes complain - that “nothing happens” in The Makioka Sisters - which offers a fascinating insight into both their expectations of novels and their view of life: because, of course, everything happens in this novel. The whole marriage thing, obviously; but also, the small anxieties and dramas of everyday life; the larger, more dramatic ones (serious illness, a flood); sex; money; status; survival: all played out against a very precisely indicated timeframe, starting in the late thirties and ending in the early years of the Second World War (before Pearl Harbour).

(Interestingly, this rather reductive viewpoint can’t be attributed to differing cultural perspectives: during the Second World War, the government censor withdrew paper for the ongoing serialisation of The Makioka Sisters because:

The novel goes on and on detailing…the soft, effeminate [sic] and grossly individualistic lives of women.1

All this, and tax codes too! Don't you just love it when civil servants wade into literary criticism? They're always so.. unassuming. And, obviously, book sold, on those criteria alone.)

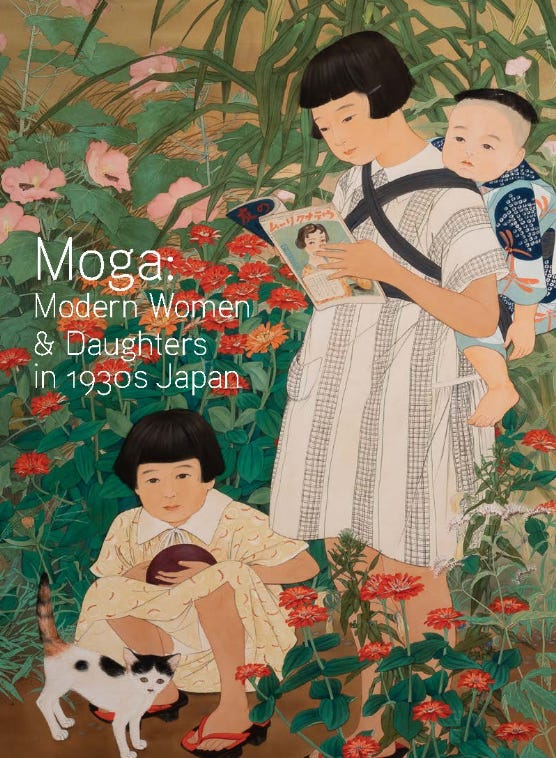

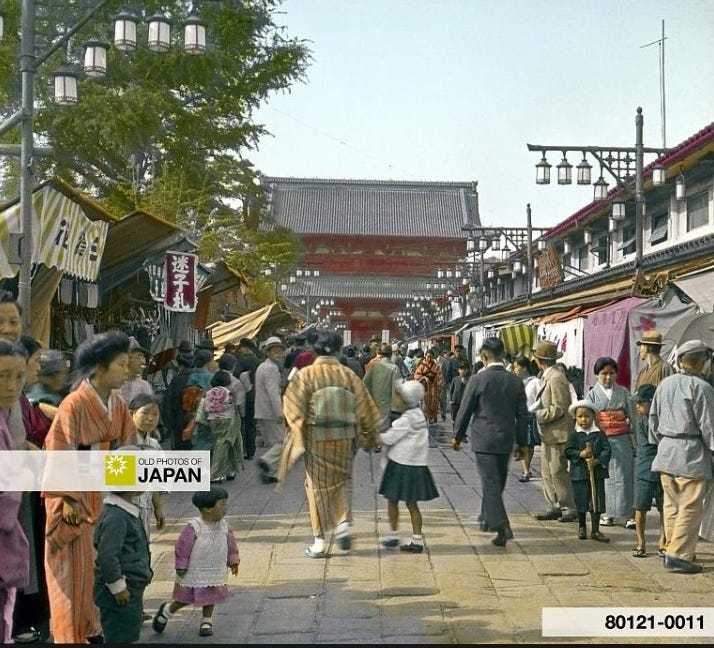

Seaming the narrative is constant tension between old and new, past and present: Japan is at a point where it engages with the modern world - both internationally and domestically - including the absorption of modern conveniences into a society still primarily governed by centuries old traditions; as well as grappling with new ways of being, exemplified by the moga (modern girl) in all her cigarette-smoking, magazine-reading, short-skirted glory as she dances to the Western popular music she plays on her gramophone. (There was also a mobo but he seems to have been rather more recessive - possibly simply because of the age-old media preference for pretty girls in short skirts as better copy.) Interestingly, Sachiko and Teinosuke's only child is a girl; so Tanizaki is setting up the potential future right there, under everyone's noses, even as he “just” writes about family life.

In some ways women were at the very core of the social and cultural tension in interwar Japan… How could one be both Japanese and modern, if modernity is defined as Western? Were modernity and Japaneseness antithetical? Or could individuals and society synthesize some new middle ground? If so, how?2

This, of course, is some of the territory Tanizaki surveys with infinite subtlety: an apparently simple tug-of-war (kimono or Western dress, say) which is actually the emblem of a society imploding; the concealed volcanic struggles which will eventually overflow catastrophically, remaking society (something he addresses in the extraordinary ending). In the meantime, it's the necessity of organising marriages, in the proper order and the proper way - and vitamin B injections, as a matter of course; the sisters self-administering whenever they think they're “low on B”. Hair and makeup for traditional formal events - done at the Shiseido Institute in Tokyo. Duty owed - and paid - to the senior house in Tokyo, even though Sachiko and Teinosuke in Osaka are more powerful in terms of actual prosperity and success. (The choice of Osaka as the location for the majority of the action is significant in itself: since the Edo period (1603-1868), Kyoto and Osaka were seen as the cultural and mercantile heart of Japan; Tokyo the centre of military culture, a destination for rustics with military ambitions, but a cultural backwater; and now, of course, the capital. The sisters’ shuttling between their apparently slow-moving, elegantly cultivated lives in Osaka and the more narrowly focused world of Tokyo, where the family honour is upheld in a cramped, rickety modern house without a garden3 (ultimate emblem of civilised existence), embodies this dichotomy. Even the Osaka accent is distinctive: broader, more expansive.) When Western guests are invited, upright chairs are provided so that they're not forced to kneel uncomfortably (good manners as well, obviously); photography is a subtle leitmotif; people move between Western and traditional Japanese dress, depending on circumstance and situation - and Taeko, the youngest and most rebellious sister, keeps her cigarette case in her obi belt: which pretty much sums it up.

(It's intriguing also to speculate whether Tanizaki actively draws on material derived from Western social narratives: early on, there's a reference to a newspaper story about Taeko’s attempted elopement when very young, misreported as by Yukiko (this potentially damaging her marriage prospects), which - it's contemporaneous - is reminiscent of Deborah Mitford's successful damages for being publicly reported as her eloping sister, Jessica3. The latter story was widely reported; and Tanizaki was very much engaged with Western culture; although, by this time, he actively espoused traditional Japanese culture.)

The novel's original title is actually Sasameyuki, which can be translated as A Light Snowfall or Lightly Falling Snow, possibly more indicative of Tanizaki's purpose (apparently, the translator was worried that it was impossible to convey the range of subtextual meaning inherent in the phrase to a Western audience; more probably, the fifties American publisher decided it “needed” a more obvious, snappier title: “Whaddaya mean snowfall, when it's about a bunch of dames?”) But in Japanese literature, snow and snowfall are often used as devices to discuss memory, the past, melancholy. Even a cursory consideration of this, opens up ways of seeing here - fallen snow (covering, blanketing, accretion/hiding): the past; falling snow (action, motion): the present; melting snow (dissolution, revelation): the future; all of which expand our reading of the novel on multiple levels; especially as - this is Tanizaki, after all - so much of what is there, is unsaid, offered to the perceptive reader in the interstices and the shadows. (If you're interested in a wider discussion of this see https://whatoreadif.substack.com/p/what-to-read-if-you-prefer-available?r=2o87f1) This is perfectly embodied in his presentation of Taeko which offers a succession of surprises, first through our acceptance (or dismissal for the most alert reader) of what is not said; then - in a gradual peeling back of the onion’s layers - through the revelations that result from seeing and understanding it. (And, of course, if it's unseen and unsaid, maybe it didn't happen.) It's a supremely sophisticated tour de force, achieved by the minutest, incremental shifts of perspective; and the cumulative effect is devastating.

There is also the merest breath of possibility - never actualised in any way - animating Teinosuke’s interest and involvement in Yukiko’s future. As a good husband, and family representative, certainly. But also… WTRI was interested to discover that an eighties Japanese film adaptation developed this strand; and, although it should also be pointed out that Donald Richie, in his contribution to A Tanizaki Feast4 vigorously repudiates this as an invented storyline; it does suggest that Tanizaki, with his usual authoritative reticence and psychological acuity, notates the bat’s squeak for those who can hear - even if it's subsequently blasted out at maximum volume, as is the way of so much film and television.

And - reverting to the novel’s title and potential meanings - also, of course, analogous to cherry blossom, a wonder and aesthetic pleasure of springtime (naturally, there’s a cherry blossom viewing sequence) - which is also closely associated with samurai, those aristocratic warriors following a strict and personal moral code, who dwindled into courtiers and civil servants; their swords no longer active but emblematic. (Which could make one think of Taeko again, with her feverish struggles for autonomy; but also Yukiko who - perhaps more successfully - aspires to something similar through ostensible passivity and conformity. Again, the uneasy tug-of-war between tradition and modernity; the apparent and the unsaid.)

And, if Taeko's cigarette case tucked into her obi belt provides the iconography of one of the novel’s principal themes; so too does the ending, with Yukiko in transit, hurtling towards her future on a train - modernity in full flight - wracked with the pangs of diarrhoea: the conflict pathologised with an earthiness that's typical of Tanizaki; whilst triumphantly embodying the unsaid. We never get to see the wedding that’s the culmination of all these years we’ve spent in the sisters’ company.

Quoted in The Makioka Sisters as a Political Novel (p. 134), Anthony Howard Chambers; A Tanizaki Feast, Univ.Michigan 1998

The Modern Japanese Woman, Kendall H. Brown, The Chronicle Review, Vol. 50, Issue 37 (2004); quoted by Kjeld Duits, Old Photos of Japan (2008/2021)

The Film Adaptations (p. 166); Donald Richie; ATF as above.

(This is an expanded version of material that has appeared earlier on Substack, in a different form.)

This post has brought to mind Madama Butterfly, maybe you can start a spin-off called "What to listen to... when you read X" I can't believe I haven't read anything by Tanazaki yet so thanks for creating a sudden urge to remedy that.

Love how much I learn from you, WTRI! And I love novels in which nothing, ie everything, happens.

And THANKS for the lovely namecheck - what an interesting Mitford allusion....